But They Only Read Graphic Novels!

I often get questions about how to "deal" with students who prefer, almost exclusively, to read comics and graphic novels as opposed to other kinds of texts. Underlying these questions (and the language embedded in the concept of "dealing with" any student) is often an assumption--fair or not--that the ultimate end goal is for students to gain enough practice reading chapter books and/or more print-heavy texts, like those they might be required to read in high school or on standardized assessments. Sometimes the concern is more benign: like with food, we want students to enjoy a balanced reading "diet," one that is infused with enough variety and nutrients that their reading brain maintains its health and important reading "muscles" do not atrophy.

For the sake of simplicity (and my sanity), I'm going to assume that, if you're reading this, you and your colleagues are already aware of the myriad benefits that reading comics and graphic novels offer readers of all ages. I'll also refrain from explaining how visual texts in all forms have typically been assigned less value than print-based texts and how, after the printing press was invented, people wrung their hands over the death of oral rhetoric and the rise of "socially isolated readers" due to the ubiquitousness of print media. I'll even ignore how just plain fun it is to read something that includes illustrations, many of which are in full-color.

Choices, choices.

The question nevertheless remains: how can we help students enjoy a balanced reading diet--one that not only values student choice, but also encourages them to read from a wide variety of genres and modalities--without also sending the (woefully inaccurate and even harmful) message that reading comics and graphic novels is akin to eating Ring Dings for dinner each night?

Here are some thoughts.

Focus on reading identity.

We all have a dynamic reading identity, and because it is dynamic, this identity develops, changes, and evolves over the course of our lives due to a whole host of factors. As part of that identity are (inevitably) areas in which we have reading gaps--genres, modalities, or types of text that we either shy away from or, for one reason or another, have had few opportunities to read. For example, one of my reading gaps has traditionally been in books typically referred to as middle grade; until a few years ago, another of my gaps could be found in books written by #ownvoices authors. I've worked really hard to close those gaps and, as a result, feel as though both kinds of books are now a solid part of my reading repertoire. Helping students to collect data on their reading choices and synthesizing that data as part of understanding their reading identity (and accompanying "gaps") can lead to setting authentic goals re: text choices.

Milk the food analogy.

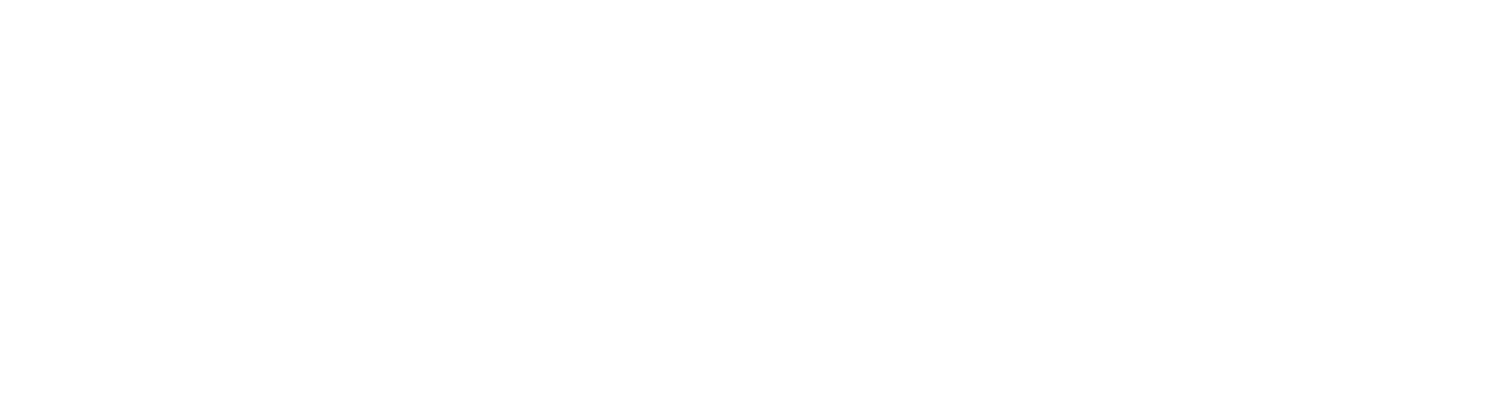

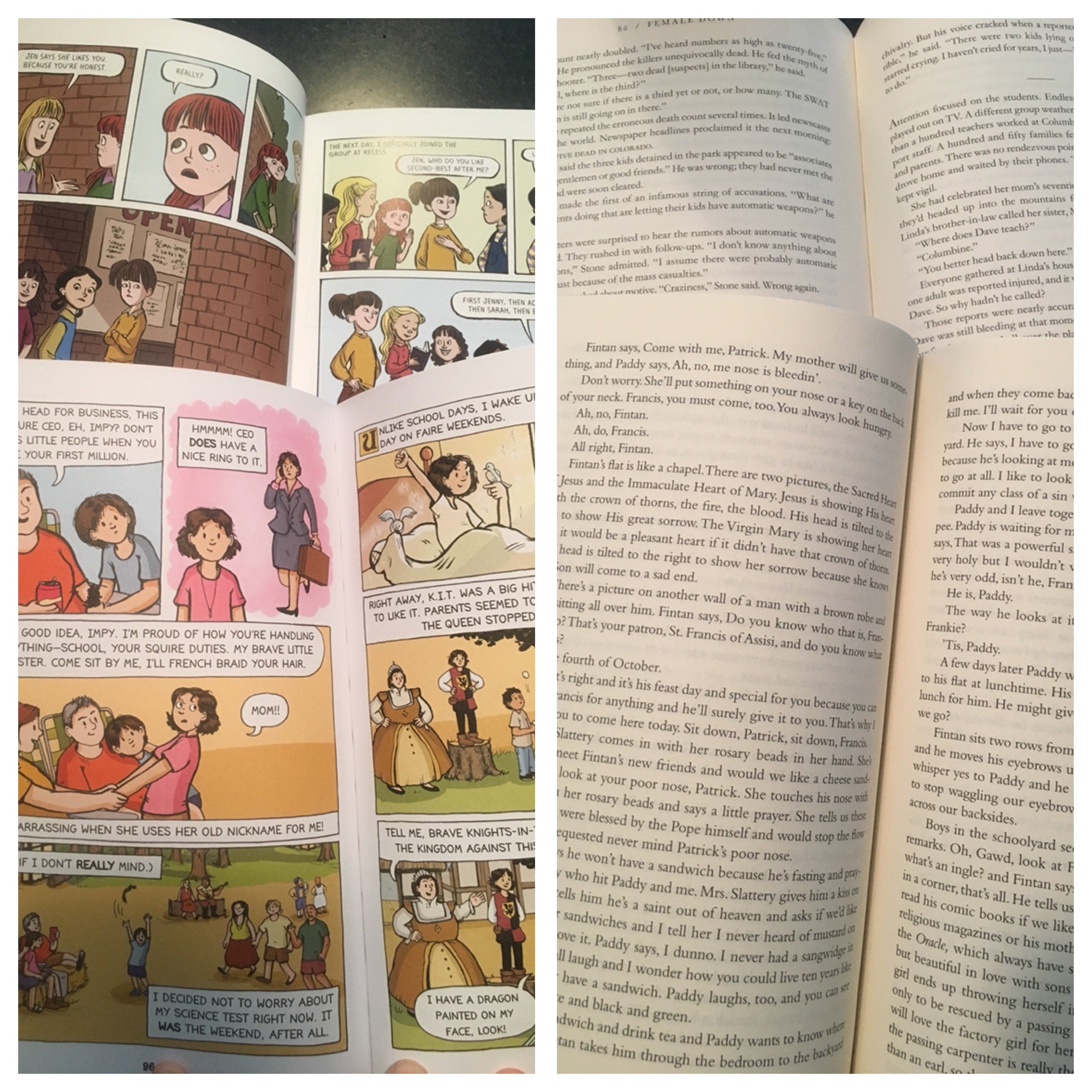

What if we compared how reading different text types/modalities nourish our brains to how different types of food nourish our bodies? For example, reading multimodal texts like graphic novels, comics, and infographics can help our brains actively engage with both print and images to comprehend a text. Reading poetry and novels in verse can help us understand how layout and concise word choice affects both the meaning of a text and the reader's experience of it. Reading informational texts, which are often saturated with content vocabulary, can help us practice deciphering the meaning of unfamiliar words and persevering through what may be a more challenging text. Each of these kinds of "nutrients" are important to our reading brain and should be reflected in our choices, at least to some degree, if we are to maintain its overall "health."

Provide authentic opportunities to read connected, print-heavy text at other times during the day (as opposed to during independent reading time).

Perhaps we ought to simply let our students read what they want to during independent reading time--including as many graphic novels as their charming little brains can handle, for Pete's sake--and be incredibly mindful about offering multiple opportunities for them to read and engage with other kinds of texts throughout the remainder of our time with them. Yes, there will (likely) always be a need for individuals to be able to successfully read a print-heavy text, and it is our collective job as teachers to move them toward such a goal. However, if we spend too much time trying to steer our students away from the texts they truly love and want to read independently, then such success will inevitably come at a cost. The price? A population of students who'd much rather skip a meal than read anything on their own.